The whirlwind rise of hyperpop

Students embrace a niche microgenre of music.

In the 1960s, beatnik icons ushered in a wave of counterculture sounds, crystallizing some of the most important psychedelic rock songs into the music scene. In the 2010s, the countercultural wave is more akin to a modern Alvin and the Chipmunks.

In 2014, an inscrutable music collective emerged, known only as P.C. Music. Out of its London headquarters surfaced a lucid, viscous brand of experimental music that seemed to perpetually glitch between “real” music and satire — the genesis of a niche, confounding pop-music phenomena dubbed “hyperpop.”

Early hyperpop releases writhe through brash, distorted bass lines, sampling saccharine synth melodies and booming percussions with the solitary goal of annihilating your ear drums. A staple of hyperpop is the earworm, heavily Auto-Tuned vocals— choruses of helium-soaked Chipmunks bounce along invigorating hooks.

Artists including Hannah Diamond, Kane West and GFOTY released new songs at an almost inhuman pace. They existed exclusively within the burgeoning digisphere, a strain of “terminally online” music that anyone with a computer editing software and a knack for the bizarre could create.

The label hyperpop seemed sensible— PC Music ringleader A.G. Cook’s shape-shifting creations eviscerated the boundaries of pop, inflating it to every possible extreme— hence the “hyper” prefix.

Yet labeling hyperpop as a subgenre is bewildering to some, stemming from the generally accepted definition of “pop” as music adhering to the rigid structure of verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus.

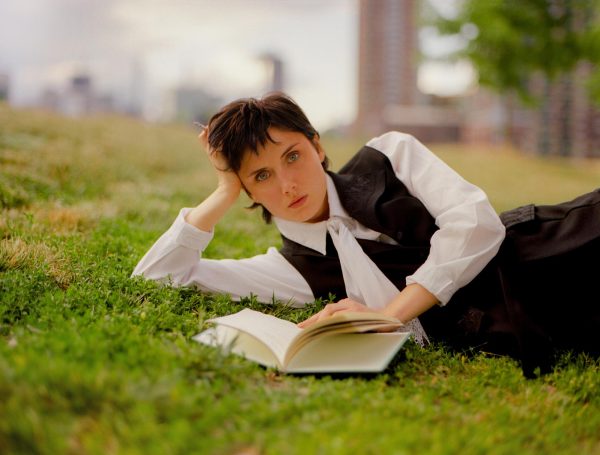

“I was showing hyperpop to [my English teacher] and he was like, ‘This doesn’t sound like a pop song at all’,” senior Lily Pesikoff said. “He thought hyperpop was supposed to be a normal radio pop at a fast pace, but what I was showing him was all over the place.”

Hyperpop intentionally eschews this conventional pop structure, opting for a formula of adrenaline-soaked chaos.

“That got me thinking about what pop even means, and if hyperpop is even an accurate term at all,” Pesikoff said. “I feel like they just put that label on it because it was a new type of music.”

Perhaps one of the most understated influences on the modern pop scene would be SOPHIE, a Scottish musical visionary who has worked with figures such as Rihanna and Vince Staples. She created her own warped pop reality, promulgating a sophisticated, hyperkinetic sound design whose blatant artificiality could be best compared to the McFlurry: garish colors, addictive texture, sticky and synthetic flavors— just pure, carbonated ecstasy.

“[SOPHIE] created a type of music that had never been heard before and has not been heard since,” freshman Turner Edwards said.

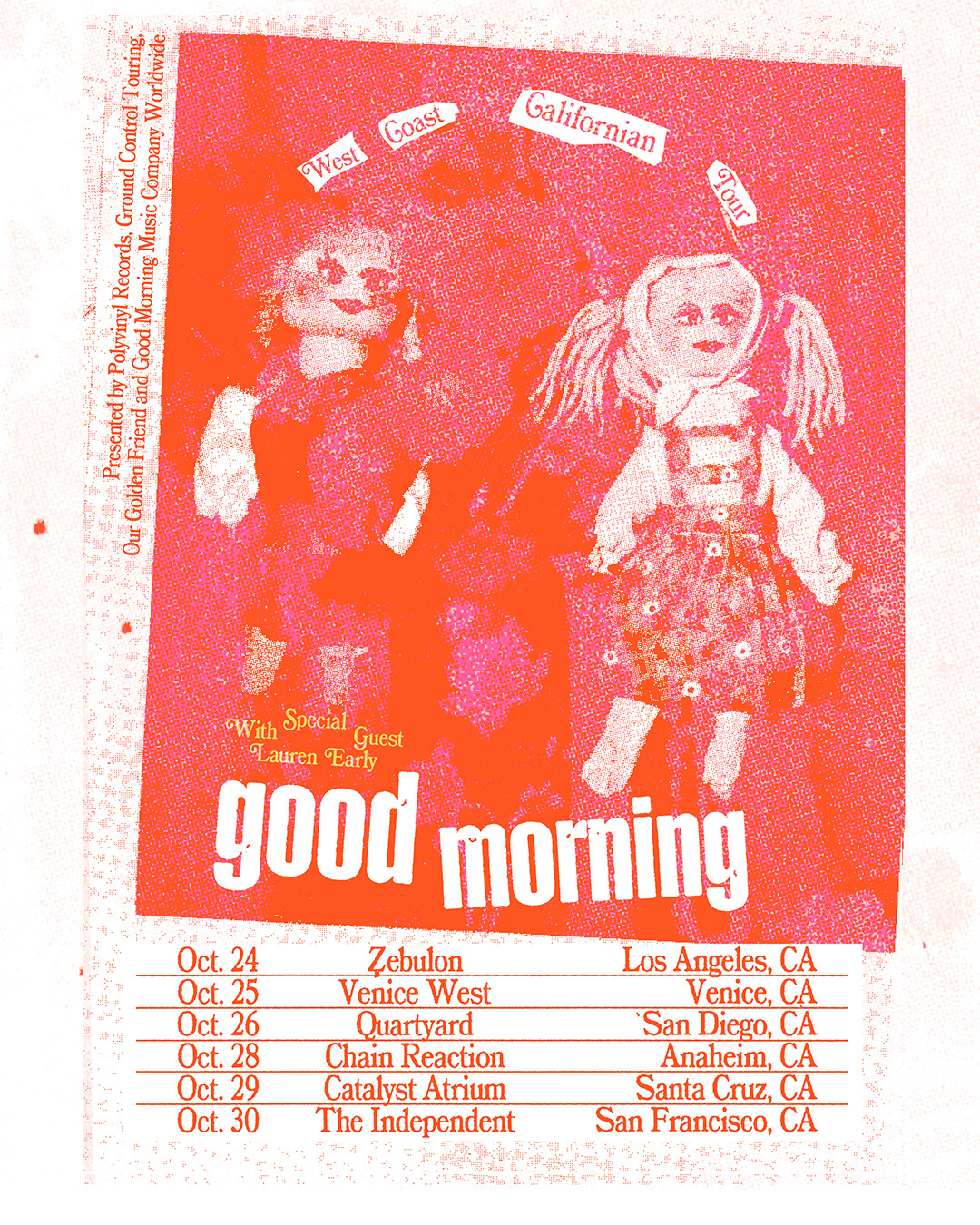

Charli XCX’s 2016 EP Vroom Vroom, which SOPHIE collaborated on, is widely regarded as hyperpop’s first venture into the mainstream. She had essentially eschewed her reign as a radio pop darling with an eclectic and electric sound.

“I guess people were really shocked with ‘Vroom, Vroom’ because it was so far from the traditional pop norm,” Pesikoff said.

Dumbfounded Pitchfork critics scored the project a 4.5, “obsessing over whether the project was satire or sincere”. In 2021, they rescored it to a 7.8.

The Internet has allowed hyperpop, an underground subculture, to penetrate the mainstream at an alarmingly rapid rate.

One of the most popular hyperpop bands of today, with over one million monthly listeners, is 100 gecs— the epitome of excellent musicians fascinated with crafting amusicalities. It’s absurdist lyrics and avant-garde mosaic of musical influences, from third-wave ska bands to the exuberant pop-punk of Blink-182, lend themselves to ambiguity.

“I listened to them once and I could not tell if it was ironic or not,” senior Jackson Harvey said.

Yet, the novelties of 100 Gecs seem to grow on many.

“I like 100 gecs because sometimes I’m not wanting to hear a specific genre, I just want to hear something crazy!” senior Stefan Gustafson said.

In response to 100 Gecs’ startling popularity came the Spotify hyperpop playlist— a constantly updating archive of the microgenre’s essentials.

The playlist straddles disparate regions of music— from the Cyborgian ballads of Arca to the angsty cloud rap croons of Drain Gang. It seems the only aspects connecting these sounds are their bludgeoning irreverence and surrealist approach to the norm of pop.

Since Vroom Vroom, then, the word ‘hyperpop’ has evolved into essentially a catch-all phrase to encompass all “weird” music.

“Honestly, I think there’s a big chance that pretty much any music that came from the internet has been retrospectively called hyperpop,” senior Will Smith said.

Beneath the grating chiptune vocals and absurdist tendencies, hyperpop songs contemplate profound subjects— corpo-humanism, gender identity, consumerism. It’s misfit aesthetic encapsulates the anti-establishment, satirizing the corporate mills of music and late-stage capitalist dystopia.

“It’s appealing in the way in which it parodies mainstream pop while also beating it at its own game,” senior Bo Farnell said.

It is ironic, then, how a supposedly rebellious genre, classified by its inability to be classified, has become so popular. For example, SOPHIE’s song Lemonade was featured in a McDonalds commercial, and A.G. Cook and Charli XCX were both contributors to Lady Gaga’s “Dawn of Chromatica” remix album. Their resistance to the mainstream has been commodified and aestheticized by that very mainstream.

“On the hate to love section on our senior questionnaire, I put 100 gecs because they are socially acceptable to love, but they have the facade of being hated,” Pesikoff said.

What else can hyperpop do than to embrace that fate?

Serina Yan ('25) joined The Review in 2021 as a freshman. Her favorite TV show is "Parks and Recreation" (but only seasons 3 to 7), and her favorite type...