How “Good Will Hunting” reveals reality of privilege, education

September 30, 2020

This summer I decided to watch as many new movies as possible to replenish my sanity. By mid-July, having watched more films in one month than I’d seen since middle school, I decided to revisit a film I hadn’t seen since then: Gus Van Sant’s 1997 multi-Oscar-winner “Good Will Hunting.”

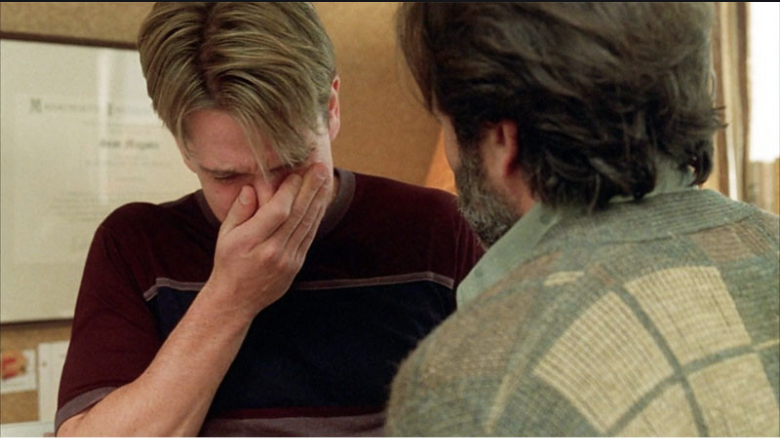

This was my fifth time watching “Good Will Hunting,” a film that showcases the efforts of self-taught genius Will Hunting (Matt Damon) to confront his abuse-filled past and discover what he wants out of life. Every viewing, a new aspect of the film jumps out at me. This time, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from Hunting’s best friend, Chuckie Sullivan (Ben Affleck).

To be clear, Hunting is a genius, and Sullivan is not. While Hunting has the opportunity to conduct groundbreaking math research under MIT professor and Fields Medalist Gerald Lambeau (Stellan Skarsgård), Sullivan will most likely be a construction worker living in impoverished South Boston for his entire life.

Ironically, Sullivan is aware of and accepts his station in life: “Cause tomorrow I’m gonna wake up, and I’ll be 50, and I’ll still be doin’ this s—. And that’s alright. That’s fine.”

Despite Sullivan’s nonchalance, “20 years” into the future, he and the countless others he symbolizes will not be “alright.” McKinsey & Company, a major consulting firm, estimates that by 2030, as many as 375 million people may be forced to learn new skills and switch occupational categories. Machines will effortlessly take over Sullivan’s job as a construction worker, and because he lacks the education to move into a higher-skill, more secure occupation, automation will render him unemployed.

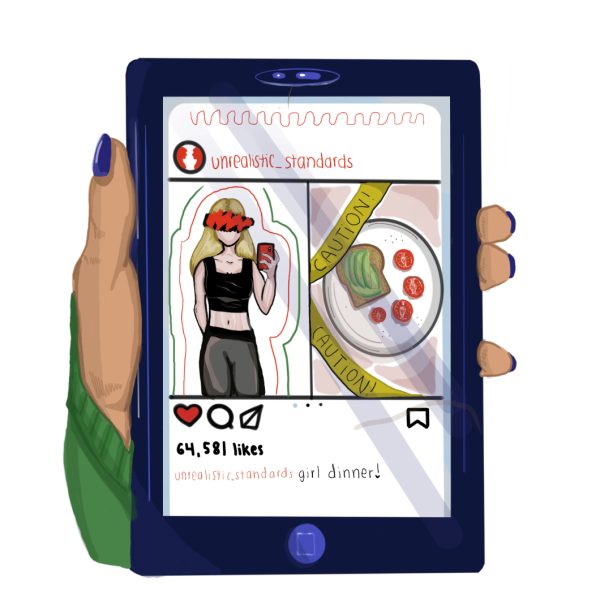

Automation is not the only threat those like Sullivan face. The pandemic certainly has increased the difficulty of putting food on the table, as employers in countless industries have let workers go. Many vital resources, including access to high-speed internet, are available only to the relatively affluent.

Although the pandemic will end, many underlying problems that hinder Sullivan will not. And the current generation will not be the last to face these challenges—Sullivan’s children may suffer a similar fate. If raised in an impoverished, working-class household without the resources for education, how will they gain the skills necessary to survive in a changing society?

The juxtaposition of Sullivan with Hunting also reveals the magnitude of privilege’s impact. If not for his chance encounter with Lambeau one afternoon in an MIT hallway, Hunting would have remained a janitor and construction worker who spends his time watching Little League baseball games and verbally sparring in bars.

Hunting is not alone; many within the SJS community might have lived vastly different lives if not for a person they met, a sight they saw or an idea they encountered. Sullivan is correct that those who are more economically and intellectually fortunate ought to be grateful for and make use of such advantages. As such, recognizing that certain privilege has helped us is an important step towards understanding the difficulties that millions, billions, around the globe grapple with every day.

An integral aspect of “Good Will Hunting,” of course, is Hunting’s struggle to realize what he wants out of life. Through examining Hunting’s interactions with those around him, however, viewers realize that the film is much, much more than the quest to help a genius blossom. It is a commentary about the necessity of receiving an education, of obtaining skills applicable decades into the future.

Without education that imparts skills applicable to a wide range of careers, the Chuckie Sullivans of the world will have no option but to helplessly watch as ever-advanced machines snatch away their livelihoods. We must all play our part in ensuring that our communities are prepared—no one, after all, is immune to innovation. And so, if given any opportunity to lift up a Chuckie Sullivan around me, just as Will Hunting’s mentors did for him, I will leap at the chance.