“Pushed toward STEM.”

Asian American students often find themselves being pushed toward STEM careers by parents who immigrated to the U.S.

“The mindset of Asian parents can be very toxic because they try to live through their kids,” Kate Vo said. “To have this predetermined path for us because of this narrow-minded idea of success is very repressive. The world is so big — we have so many opportunities.”

According to a Pew Research Center study, Asians make up 13% of those employed in STEM jobs, compared to 6% in all other fields. In 2018, Asian students earned 7% of all bachelor’s, master’s and research doctorate degrees but more than 10% of STEM-related ones.

“A lot of the time, Asian parents, mine included, want us to find a job that pays well and guarantees a good salary,” Maria Cheng said. “They don’t care as much whether we like our job.”

Rather than be pigeonholed, Cheng is motivated to pursue a career on her own terms.

“I’ve internalized the fact that I want a job that I like more than something that can pay me a lot,” Cheng said. “I would hate to work in a job that’s mindless.”

External influences often win out. Rachel Chih says that her family’s expectations significantly impacted her decision to study medicine.

“At this point, it’s so ingrained in me — what else am I supposed to do?” Chih said.

Although she comes from a family of doctors and scientists, Ariana Lee is pursuing creative writing and dance. She is co-editor-in-chief of “Imagination,” the School’s literary magazine, and a member of Terpsichore, the highest-level dance ensemble.

“I want to make my parents proud because I appreciate all they’ve done for me; I also want to keep doing the things I love,” Lee said. “They support my love for dance and writing but also strongly encourage me to pursue careers that are more stable than those in the entertainment industry. Where our interests and goals don’t align is where I feel pressured.”

Vo has never been inclined towards STEM, yet her parents have always wanted her to become a doctor or engineer.

“I was left with a little conundrum: do I pursue something that I know is high-paying?” Vo said. “I’m just not good at it, and I frankly do not find any interest in it. Where do I go from here?”

Because many first-generation immigrants are unfamiliar with English, they tend to pursue STEM over the humanities, which generally demand stronger command of language. Acquiring proficiency in STEM depends more on memorization and solving problems. These subjects also offer relative consistency; for instance, math comes in “one language — equations and numbers,” Vo said. “There’s a sense of comfort that can be found in STEM.”

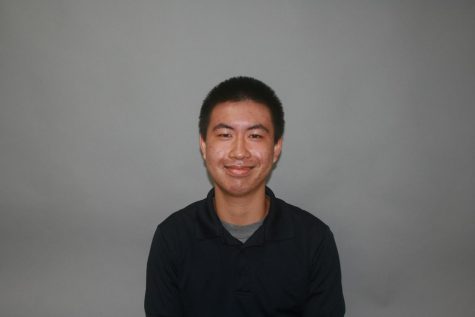

From a young age, Dian Yu’s parents emphasized the importance of math and science.

“I didn’t want to disappoint them,” Yu said, “so I went along with it.”

After she entered Upper School and joined the Junior State of America, she discovered that politics and social justice appealed more to her.

“Being in an environment like St. John’s allowed me to break through my shell,” Yu said. “I felt happier doing other things. It was just exciting.”

Beyond academics, many Asian Americans have joined debate. Vo enjoys how students engage in one-on-one or small group discourse about pre-researched topics, which empowers her to defy stereotypes and demonstrate that not all Asian Americans keep to themselves or favor STEM-related subjects.

“Debate goes against the entire idea of Asians being quiet, demure and passive,” Vo said. “It’s very satisfying to see these well-spoken Asians who are assertive take the stereotypes and reverse them.”

Because Asians are still underrepresented in the humanities, students lack role models. Without evidence that these paths are possible, many end up discouraged and default to the perceived safety of pursuing a STEM-based career.

At this point, it’s so ingrained in me — what else am I supposed to do?

— Rachel Chih

“It makes me feel a little uneasy,” Yu said. “Growing up, there wasn’t a famous Asian politician who went down the path that I want to go down.”

Yu says that Asian American participation in the humanities and social sciences is essential to change how the Asian American and Pacific Islander community is perceived globally.

“We need to be the ones writing the curriculum, history and laws,” Yu said. “We need to be in a place where our voices are heard.”

As a leader in education, Chia-Chee Chiu embodies a step toward that change. Double-majoring in ecology and English at Tulane University, Chiu knew she wanted to become a teacher since she was eight. Her parents were skeptical of this dream because teachers are frequently not held in high esteem in the U.S. Their hope that one of their three children would become a doctor did not come to fruition: her brothers went into engineering and architecture.

“It just wasn’t in the cards because we all chose different professional paths,” Chiu said. “We’re all doing well. We ultimately figured out what our passions were, and they were able to support us.”

In the first few years of her teaching career, Chiu did not see other teachers of Asian American descent. One year, after Chiu introduced herself on the first day of school, two Asian American fifth graders hugged her and told her that she was their first Asian American teacher.

“It’s important to have teachers who value and appreciate the differences that kids bring into the school setting,” Chiu said.

Lee is not certain whether she wants to pursue the careers that her parents envisioned, but she acknowledges that her parents do not want to see her struggle financially or feel unfulfilled in her aspirations.

“I have a lot of respect for my parents, even though we don’t agree on everything,” Lee said.

Vo says that her parents also look out for her best interests but wishes that they would give her more freedom to choose her path.

“They have good intentions in mind because they want the best for us, but the way they define best is not the way we define best,” Vo said.

Return to cover page.

Russell is a senior in his fourth year on Review. He's a milk tea fanatic, and whenever he's not writing or editing, he most enjoys running, eating, sleeping,...

Ella is a senior in her fourth year on Review. Her dream is to go skydiving, and she's addicted to Honey Nut Cheerios.

Ashley is a senior in her fourth year on The Review. She enjoys playing golf, baking and, to be honest, does not remember the sleep assembly.