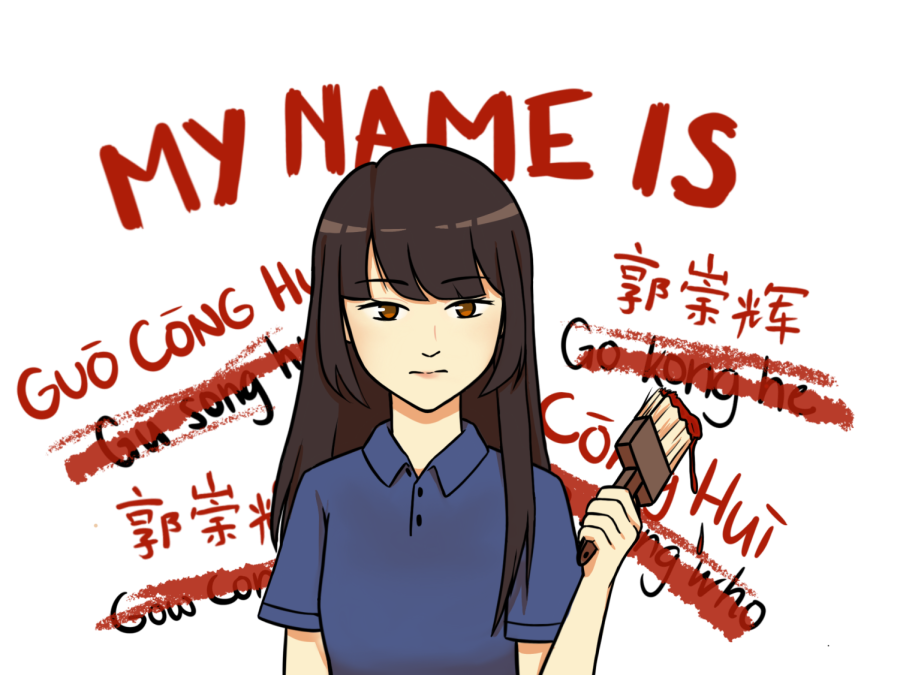

“My name got butchered all the time.”

Every time our names are mispronounced or mixed up, we feel that our individuality is denied. We understand that mispronunciation may be difficult, but making the effort to say them accurately shows that you care.

A self-described “colorful person,” junior Rachel Chih chases conspicuousness by dying her hair various shades of red and pink, creating her own custom makeup styles and alternating among a collection of over two dozen Shrinky Dink earrings.

And yet she still gets mistaken for other Asian girls.

“I must not stand out as much as I thought,” Chih said, “but am I really that unmemorable?”

Chih is not alone among Asian American students in wanting to cultivate her own identity.

Chia-Chee Chiu moved to the U.S. from Singapore when she was two. Even though she attended Miami-Dade County Schools, which had many immigrant students and teachers, people would frequently mispronounce her name.

“Kids could be mean,” said Chiu, Head of Middle School. “My name got butchered all the time.”

Senior Dian Yu appreciates those who make an effort to learn how to say her name correctly (it’s DEE-ann), but mispronunciations occur so frequently that she has stopped trying to correct them.

“If anyone screams Diane, Diana, any of these names, I will just respond because I’m so used to being called different names,” Yu said.

If anyone screams Diane, Diana, any of these names, I will just respond because I’m so used to being called different names. — Dian Yu

Close friends Remy Phan and Rayna Kim have been mistaken for each other since sixth grade. In September, the Upper School infographic mistakenly listed “Rayna Phan” as one of the newly elected ninth-grade SAC representatives. A corrected version was sent an hour later.

“Even though it’s become a normal thing for us, it’s wrong,” Phan said.

In an attempt to mitigate pronunciation issues, many Asian immigrants adopt Anglicized names. When Chiu became a naturalized citizen, she considered changing her name to Catherine but decided against it. Looking back, she appreciates the cultural significance of her first name, Chia-Chee, which consists of the same character as Chiayi, the hometown of her parents in Taiwan.

“I do like my name,” Chiu said. “It’s part of who I am and where I come from.”

Although students seldomly speak out against misnaming, it hints at the larger misconception that all Asian Americans look and behave alike, a notion that Yu considers a double standard.

“Why can white people have individual identities, while Asian kids are put together in one identity?” Yu said.

Freshman Mark Doan has seldom been confused for other Asian American students. His classmates have told him that he has “good hair and big eyes for an Asian.” Doan says that Asian American students are constantly categorized as having “one appearance, one look, one behavior.”

“People say I don’t look like the average Asian,” Doan said. “But the ‘average Asian’ shouldn’t even exist because there are so many different types of Asians with so many different types of identities.”

Return to cover page.

Russell is a senior in his fourth year on Review. He's a milk tea fanatic, and whenever he's not writing or editing, he most enjoys running, eating, sleeping,...

Ella is a senior in her fourth year on Review. Her dream is to go skydiving, and she's addicted to Honey Nut Cheerios.

Ashley is a senior in her fourth year on The Review. She enjoys playing golf, baking and, to be honest, does not remember the sleep assembly.

Alice Xu ('23) joined The Review in 2019 as a freshman. Her favorite boba order is strawberry black tea with tapioca and less ice, and she likes...