SJS alum remembers 1946 polio outbreak that prompted School closure

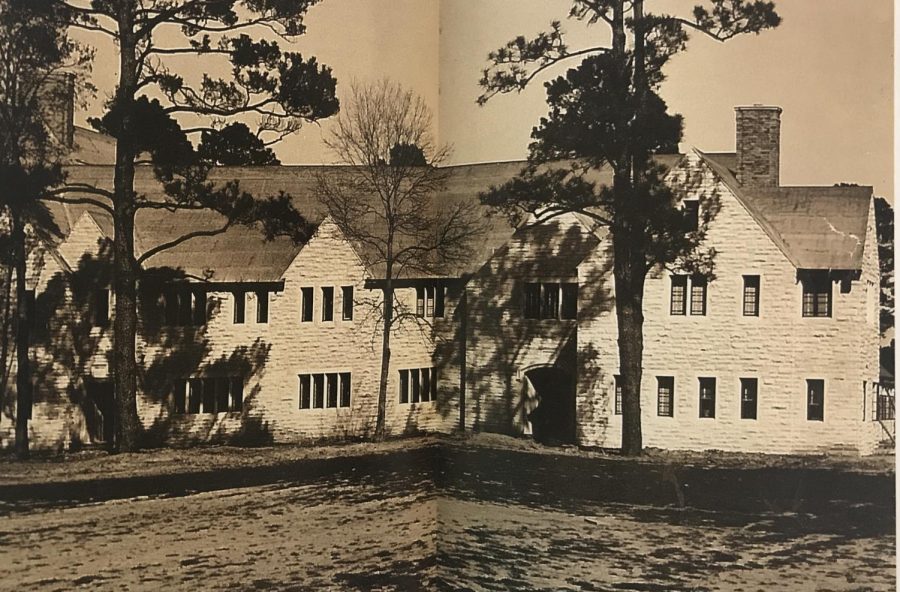

From Faith and Virtue, 1946-2012

The last time St. John’s School closed due to public health concerns was in 1946 due to a polio outbreak.

May 11, 2020

Nearly 75 years before the COVID-19 pandemic would prompt the School’s longest unplanned closure to date, St. John’s faced another viral threat: polio.

On Nov. 6, 1946, the St. John’s Board of Trustees shut down the School for a 10-day quarantine after the second community member within one week contracted polio, a life-threatening disease that predominantly affects children and can cause meningitis and paralysis.

Just the Saturday before, St. John’s teacher Betty Knepper had died of polio only one day after being admitted to the hospital. The tragedy struck mere months after the School’s initial opening in August.

“It was a distinctive event in the life of the school,” Deborah Detering (ʼ59) said. “Polio continued to be a problem, but right there in ʼ46, it very much hit home.”

Hoping to curb the spread of the disease, the Board of Trustees agreed that if any more polio cases from the School were recorded, the School would close. When another case was reported five days later, the School began what was planned to be a two-week closure.

Without digital resources like Google Hangouts or Zoom at their disposal, faculty prepared paper-based assignments that volunteer mothers would pick up from school and transport to their children back home.

Meanwhile, the polio outbreak continued to escalate across Houston. Although no other Houston-area schools reported closing, Dr. Fred Laurentz, Houston’s assistant city health officer, declared that the polio outbreak had reached “epidemic proportions” on Nov. 15. Nineteen polio cases and three deaths had been reported, setting a record for the most polio cases recorded in Houston during a 15-day period up until that point.

Polio was nothing new to Houstonians. According to The Texas Observer, between 1943 and 1954, Harris County had a polio epidemic every other year, comprising one-fifth to one-quarter of infections in the entire state. Harris County experienced more regular epidemics than every county in the nation except Los Angeles.

“Everyone knew somebody’s mother, aunt, uncle, cousin’s child that had had polio,” Detering said. “It was around, and we knew it, and everybody was afraid of it.”

Detering, mother of Shelley Stein (ʼ88), Katherine Center (ʼ90) and Lizzie Fletcher (ʼ93) and grandmother of junior Anna Center and eighth-grader Thomas Center, was in first grade in 1946. At the time, she did not realize how bad the polio epidemic really was.

“We didn’t have this 24-hour CNN talking to us about news—we didn’t even have televisions,” Detering said. “There was none of this watching every minute and statisticians up there with their charts and spreadsheets and press conferences. There was every now and then an update in the newsreels at the movies.”

Lacking the knowledge base that researchers today have on COVID-19, medical professionals and healthcare officials alike knew little about the causes of polio when the disease peaked in the 1940s and early ’50s. The first vaccine did not go into widespread use until 1954.

“It was a whole other world,” Detering said. “They were just flying blind.”

Following the November outbreak, Laurentz announced that antipolio DDT spraying would begin again in an attempt to contain the virus. DDT was an insecticide that the U.S. government banned for use in 1972. Equipped with two DDT power sprayers, a crew of four men would spray premises wherever polio broke out, as well as ditches, alleys and houses adjoining the break-out spot.

In order to prevent the accumulation of crowds, public swimming pools often closed during the summer months when polio seemed to thrive the most. In a largely pre-air-conditioning Houston, the loss of these pools was particularly unbearable.

“That was a way you kept cool here other than going home and taking a nap under a fan,” Detering said.

One of Jim Greenwood’s (ʼ54) River Oaks neighbors even built a swimming pool specifically so that the family would not have to go to the River Oaks Country Club or a public pool to cool off.

Like many other Houstonians, Detering’s family traveled west into the Hill Country during the summers in an attempt to escape the virus. By holing up at dude ranches during peak polio season, families hoped they could escape the mugginess of Houston and keep their children safe.

“Mother kept saying, it was hot out in West Texas, but it was dry air,” Detering said. “We thought we were fine.”

In December 1946, Basil O’Connor, president of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, said that nationally, the 1946 polio epidemic was the worst of its kind in 30 years. Contemporary reporting in The Texas Tribune placed the number of 1946 cases at 27,000 across the U.S.

Because polio cases tended to die down during the winter months, Laurentz could not explain why Houston’s November 1946 epidemic was so severe.

Despite polio’s prevalence, Detering does not remember there being as much “daily panic” compared to the COVID-19 crisis today, due in part to the lack of understanding of how the disease worked.

“There wasn’t the sense that if you went to the grocery store, you were going to catch it,” Detering said. “I don’t remember it being discussed that much around the table. They didn’t talk about what they had no way to solve.”

According to Detering, polio in the 1940s seemed nearly unpreventable, while today people maintain hope that researchers will develop a vaccine.

“We expect better healthcare now—we are unwilling to have people simply get sick because we don’t have a cure,” Detering said. “With polio, a lot of people were going to die, and we just had to accept that. Nobody wanted to get polio, but it wasn’t like there was anything you could do about it.”

Having infected more than 1.3 million people across the U.S., COVID-19 has had a similar, if not larger, physical impact than polio did at its peak.

“We’re not going to West Texas for the spring, but we’re sitting here in our houses for spring break, and all I can hope is maybe that will flatten that curve for us,” Detering said.

Rachel Gillett • May 18, 2020 at 11:13 PM

I really enjoyed this, Abigail! Wonderful article!

Deborsh Detering • May 12, 2020 at 8:21 AM

Wonderful article. I learned a lot that I did already not know.

Linda Woods • May 12, 2020 at 7:02 AM

Thank you Abigail. So well written and interesting to compare then and now. Great choice of subject matter for your article. Such fond memories of you.

Addison Spiegel • May 11, 2020 at 10:42 PM

Very interesting. Did not know that this happened.

Mary Pollock • May 11, 2020 at 7:19 PM

Wonderful article Abigail!