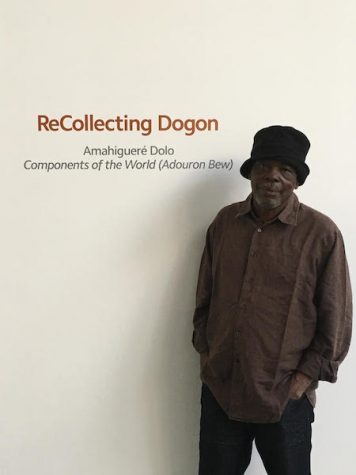

What I learned at the art exhibition “Recollecting Dogon”

Dolo’s piece “Components of the World” consists of shaped wood pieces in red soil.

February 28, 2017

Growing up in Mali, Amahiguere Dolo was discouraged from pursuing his passion for sculpting because he came from a family of farmers. He left the country to chase his dreams and today has artwork featured worldwide, including a piece at the Menil Collection in Houston.

The French AP Language and AP Literature classes took a trip to the Menil on Feb. 15 to hear Dolo discuss his work and life journey in French. This trip drew on the themes of cultural art that the AP exam covers.

Dolo’s complex and beautiful piece, “Components of the World,” initially seemed like a random arrangement of twisted pieces of wood stuck in red soil. The deeper meaning behind this work became clear through Dolo’s careful, softly spoken explanations. Vaguely lifelike forms of pregnant women, animals, and insects took shape out of the previously meaningless wood pieces.

AP French and French Literature students visited the Menil on Feb. 15, exploring themes of cultural art that the French AP exam covers.

Instead of carving shapes from wooden blocks, Dolo would search across Mali for wooden pieces that naturally resembled these images. This way, the beauty of the wood was able to shine through his work. Nothing about the sculpture seemed forced–observing the piece felt almost spiritual.

Dolo’s installment was just one part of “Recollecting Dogon,” an exhibition featuring several artists and sculptors from West Africa that will end July 9. The collection focused on Western perceptions of African art, the legacies of colonialism, and the limitations of representing African culture through Eurocentric media or literature. In many cases, the Western perspective emphasizes certain aspects of African art while ignoring other nuances. For instance, features such as dark skin are exaggerated, and the subjects are often portrayed as primitive. Such perspectives further promote stereotypes of African cultures and people that many Westerners already believe.

Dolo’s work was part of the exhibit “ReCollecting Dogon,” which spotlighted West African artists while exploring how Westerners perceive African art.

Near the center of the exhibit hall sat a sculpture of a man the size of a book created out of dark metal. Delicate details filled the surface of his skin as well as the stool he sat on. Behind this sculpture were two pictures of the same sculpture taken by a United States-based photographer. The photographs were edited in a way that made the statue look significantly darker and devoid of interesting detail. They essentially washed away the sculpture’s uniqueness. The images seemed flat and lifeless compared to the vibrant statue sitting before me.

I walked out of the museum with an appreciation for the richness of African culture and a look into the mind of a fascinating sculptor. Visiting “Recollecting Dogon” made me realize that, while viewing another culture through our own cultural lens may offer new insights, it’s important to always go back to its roots ― the original artwork, the first written word, the unedited song ― in order to gain a full understanding.