Fashion double standards displace culture

Who wore it better?

April 20, 2017

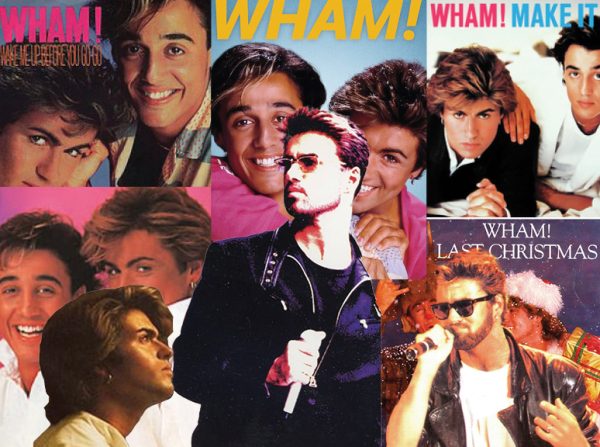

In March, Vogue celebrated diversity by featuring six pages of model Karlie Kloss dressed as a geisha. Meanwhile, black model Imaan Hammam and Chinese model Liu Wen warranted only one photo each.

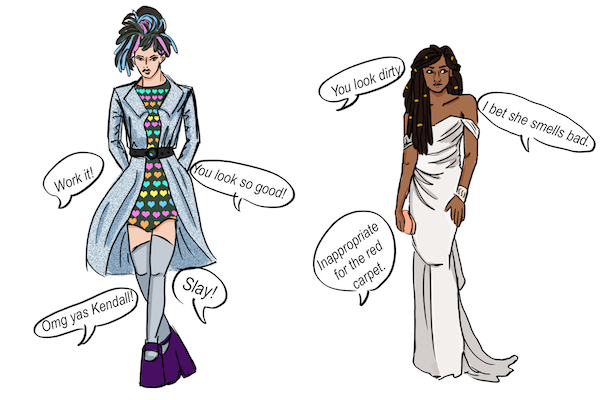

In September 2016, Marc Jacobs introduced his spring 2017 collection by sending porcelain-skinned models down the runway sporting fake dreadlocks. When Zendaya, a black singer, wore the same hairstyle a year earlier, Fashion Police co-host Giuliana Rancic mocked her hair and said that it smelled of “patchouli oil” and “weed.”

It is frustrating that the beauty industry has used minority cultures as an aesthetic without paying much credit to those cultures.

Karlie for Vogue US – March 2017 pic.twitter.com/Pbo9rssT8p

— bestkkpics (@bestkkpics) February 14, 2017

https://twitter.com/fuzzybee1234567/status/831639628579033095

For marginalized groups, our cultural habits are deeply intertwined with our experiences. “Trying out” a culture places it out of context. Seeing the custom so detached from its origins has just never made sense to me.

There are people of color who completely support these actions or don’t care. That does not invalidate the fact that double standards exist in the beauty industry. Reactions may vary, but the truth does not change: racial dynamics influence beauty standards.

Jacobs responded to criticism about his show by saying, “Funny how you don’t criticize women of color for straightening their hair.” Jacobs fails to distinguish between appropriation and assimilation. We can’t appropriate a culture that is already established as the norm. We can only conform.

The Perception Institute, a national group that conducts psychological research on gender, race and ethnicity, conducted an Implicit Association Test in 2016 to assess bias against black women’s textured hair. Of nearly 4,000 participants, the majority showed an implicit bias against black women’s textured hair, and over 60 percent of white women rated it as less beautiful and less professional than straight hair. Research firm Mintel estimates that the black hair straightening industry generated $684 million in 2012.

I don’t doubt the facts — my African-American friend once wore cornrows to work and was told that her hair had to be changed.

Minorities often hide features they are born with in order to seem more attractive and more professional. Imagine the frustration of seeing those same features celebrated on white models strutting down a runway. There’s a reason why Marc Jacobs did not feature any of the numerous models of color who have real dreadlocks and why Vogue did not ask a Japanese model to portray a geisha. Many people would rather see a white person showcasing a minority’s culture than the minority doing the same thing. The cultural styles we praise as high-fashion on white models are mocked on those from the culture of origin.

People can be genuinely interested in other cultural experiences, but there is a difference between appreciating a culture and exploiting it.

If we credit white fashion designers for their ideas but claim that ethnic groups have no ownership over their distinct cultural styles, then we marginalize them. If we validate the beauty of a culture only when removed from its people, then we marginalize them. Most importantly, if we borrow from a culture but remain silent about the social problems that affect them, then we permit moral dissonance.

Many people would rather see a white person showcasing a minority’s culture than the minority doing the same thing.

I’ve encountered people who wear Native American headdresses as a fashion statement but couldn’t care less about the Dakota Access Pipeline. How does one aestheticize another culture without supporting its people? Appropriation does not pay homage to a culture when that culture is not respected in the first place.

Accusations of political correctness plague the conversation about cultural appropriation. It’s easy to think that way. Compared to racially-charged hate speech and violence, simply wearing a costume seems innocuous, but it stills reflect a system through which minorities are perceived as lesser.

There is no obvious harm in dressing like a “sexy geisha” on Halloween, but the ideas driving that choice speaks volumes about how people perceive Japanese women. Racism is so deeply instilled in our society that people sometimes don’t realize when they are perpetuating it. That is why we must recognize the implications behind the action. Racism does not have to be explicit to create inequalities.

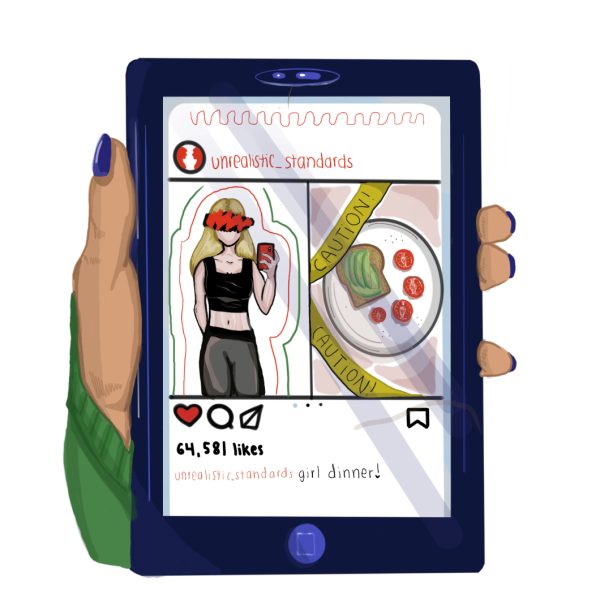

If we educate ourselves and respect other people, sharing cultures can actually help us evolve. Learning the history and supporting the people behind a culture is much more interesting than just using some “exotic” accessories for an Instagram pic. Beauty has its origins. Let’s recognize them.

Read this article in the April issue of the Review!

AmoyLily • Apr 25, 2017 at 2:20 AM

I always think that different culture can bring us a different sense of fashion. But as you say, we should respect their social customs and habits.

AmoyLily